‘Come on the Bolsheviks‘

The Kinmel Park Riots

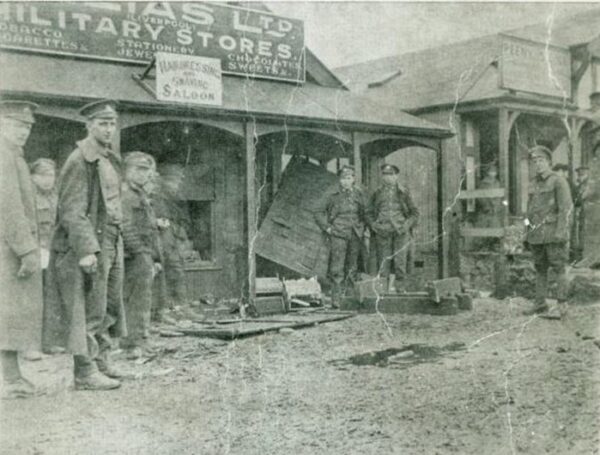

On Tuesday night, the men held a mass meeting, which was followed by a mad riot. The outbreak began in Montreal Camp at 9.30 p.m. with a cry ‘Come on the Bolsheviks’, which is said to have been given by a Canadian soldier who is Russian.

Kinmel Park Court of Inquiry

Sapper William Tarasevich

Sapper William Tarasevich born in Grodensky Gooberni, Kobainskago Nyder, Russia on 22 February 1889. Next of kin mother Mary Tarasavich of Motolskoy, Poloste, Russia.

William enlisted 3 January 1917 in Montreal, standing 5′ 9″ tall, 168 pounds, 27 years and 11 months of age with sallow complexion, light blue eyes and brown hair. William was Greek Orthodox.

Prior to departure for England, Sapper William Tarasevich forfeits 2 days pay and allowance and awarded 4 days CB in February of 1917.

245th Battalion Grenadier Guards

The 245th Battalion organized in June 1916 under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Colquhoun Ballantyne (a millionaire and one-time owner of Sherwin Williams Paints in Montreal). Mobilized at Montreal and also recruited in the Montreal district. Embarked from Halifax 3 May 1917 aboard JUSTICIA, and later disembarked England on 14 May 1917 with a strength of 16 officers, 274 other ranks. Absorbed by 23rd Canadian Reserve Battalion on 14 May 1917.

Sapper William Tarasevich embarked Halifax per HMT JUSTICIA on 3 May 1917, later disembarking at Liverpool on 14 May 1917, and transferred to 23rd Reserve Battalion.

23rd Reserve Battalion

23rd Reserve Battalion organized at Shorncliffe on 4 January 1917 initially under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Frank William Fisher. Formed by absorbing 23rd and 117th Battalions. Absorbed 244th Battalion on 24 April 1917, 245th Battalion on 14 May 1917. Moved to Shoreham on 5 January 1917, Bramshott on 11 October 1917 and finally Ripon on 2 February 1999.

VDG

Sapper William Tarasevich admitted 30 May 1917 at Etchinghill, NYD, and later discharged on 21 June 1917.

Admitted again on 12 September 1917 at Barnwell Military Hospital, Cambridge, VDG. A long ‘recovery’, finally discharged from Cherryhinton, Cambridge, on 4 March 1918.

4th Canadian Railway Troops

William Tarasevich ToS 4th Battalion CRT at Purfleet on 28 March 1918.

4th Battalion, Canadian Railway Troops organized at Purfleet in January 1917 under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Chilion Longley Hervey. Arrived in France 24 February 1917.

AWOL

Sapper William Tarasevich sentenced to 3 days FP No 1 on 2 October 1918 for AWOL on 8 August 1918.

Accidentally injured

Sapper Tarasevich to No 6 Cdn Fld Amb, 3 November 1918, injury to face and hand (accidental). No 23 CCS to No 4 General Hospital, Camiers, 6 November 1918. To No 6 Conv Depot, Etaples, 10 November 1918. Discharged on 15 November 1918.

4th Reserve Battalion

Organized at West Sandling on 4 January 1917 initially under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Frank Case McCordick. Formed by absorbing 35th Canadian Reserve Battalion, one-half of the 162nd and one-half of the 168th Battalions. Absorbed 160th and 161th Battalions on 15 February 1918, and 186th Battalion on 10 April 1917. Moved to Bramshott before April 1917. Absorbed 25th Canadian Reserve Battalion on 15 February 1918.

Sapper William Tarasevich ToS 4th Reserve Battalion at Witley on 30 January 1919. Leave with free warrant on 1 February 1919. SoS 4th Reserve Battalion on transfer to Wing No 11, Kinmel Park, 17 February 1919.

Kinmel Park

Reported by Surgical at Kinmel Park, Sapper William Tarsevich accidentally killed, 5 March 1919.

The Riot

On the evening of 4 March 1919 at around 9:00 PM, approximately 1,000 troops rebelled and started a riot. The idea likely came from a strike that the British troops staged a few months earlier, resulting in their early demobilization.

Once the riot started, it quickly got out of control. It started with one of the canteens, spread to a sergeant’s mess quarters and then into “Tintown,” where the troops took their revenge against the local profiteers.

The mutineers remembered their debt to the Salvation Army, and these quarters spared. The YMCA, and the Navy and Army Canteen Board (NACB) viewed to have inflated prices, resulting in their buildings being looted and damaged. The overall damage calculated to be in the thousands of dollars, with stolen or destroyed clothes, food, alcohol, cigarettes, tobacco, and equipment.

5 March 1919

The camp defenders clashed with the rioters and seized 20 men. An attempt to liberate prisoners thwarted. The violence continued. Shots fired, and the two sides engaged in hand-to-hand fighting that included the use of bayonets. The rioters finally surrendered after three of their number killed or mortally wounded. Two guards also died during the riot. Twenty-three men wounded.

Aftermath and Significance

Kinmel Park Riots one of thirteen disturbances during demobilization. In total, 78 soldiers arrested, of whom 59 faced court martial under the British Army Act. Twenty-five convicted and sentenced to terms ranging from 90 days in detention to ten years in prison for one soldier. Some of the more severe penalties later reduced. No one charged for the deaths, as inquiries proved inconclusive. Most of the men in Kinmel Park Camp sent home by the end of March 1919.

Five Canadians killed in the subsequent encounters, and 23 wounded. The names of the five killed.

- Railway Trooper William Tarasevitch

- Corporal Joseph Young

- Private David Gillan

- Signaller William Haney

- Gunner John (Jack) Frederick Hickman

Surprisingly, one of those killed in the riot buried in Canada.

Gunner John Frederick Hickman

Gunner John Frederick Hickman 326914 born in New Brunswick, Canada. He enlisted in April 1916 and served in France with the 58th Battery, 14th Brigade CFA from July 1917. During the riot, John in his tent, not participating in the disturbances. It appeared that he had been killed by a ricochet bullet through the heart and later exonerated from any part in the riot.

Son of Mr and Mrs John Howard and Theresa Hay Hickman, of Dorchester, N.B. John’s mother died in 1917 while he was overseas. His father died in 1921, both also buried in Dorchester Rural Cemetery.

Repatriation

Hickman an extremely rare and late instance of repatriation in the Great War. More common among those rare instances to be an Officer of an affluent family, than an Other Rank. John’s service record gives no indication as to how or why his body repatriated.

John a descendant of William Hickman, and his name appears on the Dorchester War Memorial, Dorchester NB, Canada. His family history reveals he was from an affluent family.

The Hickmans of Dorchester

The Hickmans of Dorchester merchants and businessmen involved in politics and community organizations. However, as shipbuilders they acclaimed a world-renown reputation. In 1878, and for a few years thereafter, Canada could claim the fourth largest merchant marine in the world.

Reported that approximately 30 shipbuilders have built over 80 vessels in Dorchester in the 19th century. William Hickman reported to have built up to 25 vessels at Dorchester Island and four in Hillsborough. Finally, William Hickman one of the most innovative and prolific ship builders in Atlantic Canada.

Marlene and her husband Robert Hickman, a direct descendant of John Hickman, currently live in the Hickman family home built in 1834.

“He was an innocent bystander and was killed in his tent.”

Marlene Hickman

The other four of those killed in the course of the disturbances buried in the nearby churchyard of St Margaret’s Church at Bodelwyddan.

St Margaret’s Church at Bodelwyddan

For 83 Canadians of the Great War, Bodelwyddan their final resting place. Most of the men who lie in the graveyard alongside the bustling A55 highway victims of a deadly outbreak of influenza.

Over the years the stories told and retold locally of the Kinmel Park riots have had a tenuous link with the truth.

“It’s a Chinese whisper sort of thing”

Rev. Berw Hughes of St. Margaret’s Church

St. Margaret’s Church, also known as the Marble Church because of the amount of marble lining its interior.

Private David Gillan

Private David Gillan 877467 born in Lanarkshire, Scotland. His family had emigrated to Canada in 1903 and had enlisted in Nova Scotia in March 1916, serving in the 85th Battalion in France from March 1918.

During the riot, David was on guard duty and sustained a bullet wound to the neck.

Gunner William Lyle Haney

Gunner William Lyle Haney 1251417, 78th Battery, CFA, born in North Dakota, USA. He enlisted in Calgary in February 1918 and had served at Witley Camp in England. He was killed by a bullet wound to the head. Captain Kerfoot had also performed his autopsy.

Private Joseph Young

Private Joseph Young 438680 born in Glasgow. He enlisted at Port Arthur in April 1915 and served in France with the 52nd Battalion from February 1916.

Young had been sanctioned for being AWOL or drunk seven times before departure to England. Admitted for influenza, trench fever and VDG in 1917. Promoted twice in the field.

At the time of the riot, Young in Segregation Camp at Kinmel Park. Joseph participated in the riot, and died of a bayonet wound to the head less than two hours after being treated by Captain Kerfoot.

The inscription on his grave words from the refrain of a hymn composed by Maxwell Cornelius in 1891 of which the second verse may be better known.

‘We’ll catch the broken thread again.

And finish what we here began,

Heav’n will the mysteries explain,

And then, ah then, we’ll understand’.

Sapper William Tarasevich

John Babcock

John Babcock died on 18 February 2010 at age 109, Canada’s last surviving soldier of the Great War. He enrolled at 15 and eventually made it to England. When his age discovered, transferred to Kinmel Park Camp along with other underage soldiers.

Although Babcock not involved in the March 1919 riot, he and his friends did cause some trouble while at Kinmel. Shortly after the armistice signed in November 1918, they were prevented from entering a dance by a bunch of British officer cadets. Babcock and his friends charged the hall, armed with an assortment of bricks and sticks. After a bit of property damage and a few non-lethal injuries, their officers convinced them to return to quarters.

Nursing Sister Rebecca MacIntosh

One of the CEF whose ghostly footsteps may still be heard in Bodelwyddan – Nursing Sister Rebecca MacIntosh, who died at No. 9 Canadian General Hospital in Kinmel Camp on 8 March 1919. Daughter of Mr and Mrs Peter O MacIntosh, of Pleasant Bay, Inverness Co., Cape Breton, Nova Scotia.

“Nursing Sister MacIntosh of this unit died in hospital today—influenza. This sister was very popular with the unit; a true nursing sister devoted to her duty. She will be greatly missed by all.”

No. 9 Canadian General Hospital War Diary

In 1914, Rebecca survived a serious bout of scarlet fever. By 1917, well enough to enlist in the CAMC. Her father had died and her mother living in Bridgewater, Lunenburg County, likely with her son John. Rebecca buried in St. Margaret’s Cemetery on 9 March 1918.

Sapper William Albany

Son of Peter A. Albany, of Latchford, Ontario. Sapper Albany an Algonquin from Point Pine, Temiskaming, Ontario. Sapper William Albany 1007062, enlisted on 13 December 1916 at New Liskeard, Ontario.

William enlisted into the 256th Battalion of the Canadian Railway Troops in January 1917 under the command of Lieutenant Colonel W A McConnel. Re-designated as the 10th Battalion on 30th May 1917, they arrived in France on 19 June 1917.

Sapper Albany taken ill with Influenza on 7 December 1918 and transferred to hospital in Boulogne where he received treatment but then deemed to be seriously ill and transferred back to England and arrived at Bordon Army Camp on 16 December 1918. Shortly after arrival at Bordon, William transferred again to Kinmel Park Camp in Rhyl where he was admitted to Number 9 General Hospital on 6 February 1919. He developed Bronchial Pneumonia and died at 3.40 hrs on 10 February 1919.

The Court of Inquiry

The Court of Inquiry conducted its initial investigation at Kinmel Park Camp immediately after the mutiny and later reconvened at the Overseas Ministry Headquarters in London on 31 March. The findings of the Inquiry attributed the causes of the mutiny to a number of issues.

Causes of the Mutiny

- Delays and postponements of sailings coupled with rumours of cancellations until the 3rd Division returned to Canada provoked great discontent. This was coupled with the last sailing previous to the mutiny being 25 February and no information regarding future sailings arrived prior to 4 March, too late to assuage the discontent.

- Soldiers had an impression that their stay in Kinmel Park Camp would be brief, which was not always the case and coupled with these extended stays was the administrative issue that individuals did not receive pay after their initial repatriation

issue until embarkation for Canada. - The Court mentioned that some soldiers experienced delays in repatriation due to loss of personal documents.

- There were delays in pay also attributable to lost papers.

- An inability to procure tobacco on credit was referred to as a problem.

- Poor food due to a lack of qualified cooks was cited as a contributing factor.

Private Archibald Laing Wallace

Private A L Wallace 28099 of the 15th Infantry Battalion testified.

I registered in this Camp on 21st February 1919. I live in hut 15 in sailing Lines, M.D.2.

I am a re-patriated prisoner of war (released 30-11-18).

The situation in this camp as I understand it was this. There were the usual murmurings of soldiers, there were discomforts of various sorts, many men were broke and couldn’t buy cigarettes or soap, but we were all looking forward to get away home and all these things were suffered with the hope in view of something better to come in the shape of sailing for home.

Private A L Wallace

Cancellation of sailings

Then came the cancellation of sailings – then came the news that the 3rd Division was going home first – that they were the fighting division of the Canadians this was the climax. On the day before the riot it was on everyone’s’ lips – it was a general feeling – every man I met was talking the same thing.

I do not think it was organised, but once the thing was started others joined in and it turned into a demonstration about the sailings being cancelled and it became a protest designed to reach the attention of the highest authorities.

Private A L Wallace

Pay secondary

The sailings were the real cause – the want of pay was secondary. In my hut I don’t think there was five shillings among the 30 men. One man had not received pay since 5th Feb. I had not received pay myself since 8th February, but personally I have no complaint about pay. I have drawn $300 since coming back from Germany. I have still some $600 coming to me. I knew I could have drawn pay at any time.

I think if the men had been told about the sailings, why they were postponed or cancelled there would have been no trouble. The first explanation given us was by Gen. Turner. Now it is posted on boards. – things are improved. Had the men known the true situation they would have thought different.

Private A L Wallace

Private Wallace’s compatriots made similarly cogent observations regarding the flow of information.

Corporal George John Clout

Corporal G J Clout 1099030 of the 10th Canadian Railway Troops testified.

I have been addressed by Officers about the regulations as to pay since the riot – not before. Orders were read out. Previous to the riot we had no explanations about cancellations of sailings – nor about the washing system – nor about requiring a pass to go to Rhyl – nor about dress.

Corporal G J Clout

Later a different soldier was questioned as to the probability of disturbances when he was processed at Kinmel Park three weeks previously.

Oh yes, I was sure a riot would break out any time. There was a lot of grousing. In fact, the soldiers said there’d be a riot if they did not get away.

Anonymous Soldier