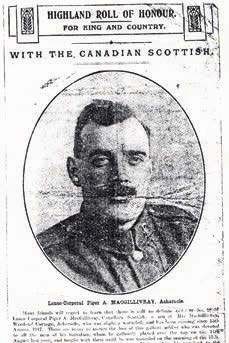

LCpl Alexander MacGillivray MM a piper killed at Hill 70 who refused to draw lots. “He would go in anyway.”

Any piper who had grounds for suspecting he had been discriminated against in the ballot, taunted his comrades with injustice, and insisted on accompanying the attacking troops. Brave men, who met death when it came to them unflinchingly.

Acharacle

Alexander MacGillivray, son of John and Flora MacGillivray, of Woodend Cottage, Acharacle, Argyllshire, Scotland. Born 5 January 1888 in Acraracle, Agrgyllshire, Scotland. He was a labourer and single when he came to Canada and enlisted with the CEF.

Scottish Regiment

Private Alexander MacGillivray 28557 enlisted 23 September 1914 at Valcartier, QC, Canada with 72nd Regiment, Seaforth Highlanders. A big man, standing 5′ 10″ tall, 175 pounds, with fair complexion, blue eyes and brown hair. Immediately placed on 16th Battalion paylist.

16th Battalion (Canadian Scottish)

The 16th Battalion (Canadian Scottish Regiment) organized in Valcartier Camp in September 1914, composed of recruits from Victoria, Vancouver, Winnipeg and Hamilton. Commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel R G E Leckie. Embarked Quebec 30 September 1914 aboard SS ANDANIA, and later disembarked England 14 October 1914 with a strength of 47 officers, 1111 other ranks.

France

Pte Alexander MacGillivray granted 7 Days Leave on 20 November 1915.

Private A MacGillivray appointed Lance Corporal in the Field, 10 March 1916.

Lance Corporal Alexander MacGillivray admitted to No. 26 General Hospital, Etaples (Influenza) on 31 August 1916 and later discharged from No 6 Convalescent Hospital, Etaples on 8 September 1916.

Military Medal

Hill 70

As far as the 16th men concerned, their conduct in the fight left little to be desired. The calm, collected attitude of the Battalion toward the ordeal of battle well typified in the following incident in No Man’s Land just after the assault launched.

One of the noncommissioned officers, in rushing towards the enemy’s line, got his kilt caught in the barbed wire. He fell face downward on to the wire and muddy ground. On getting up he found alongside of him one of his men in same predicament. They stood for a moment, grimy and blood-stained. Looking at each other, the private said, “Well, Mac, I guess if you and I were hung for beauty now, we would be innocent men.”

Pipers

The pipers came up to their usual standard of coolness and gallantry. Before the attack started Piper Alexander MacGillivray told the sergeant major, in confidence, that he felt “anxious.” He was afraid that, burdened as he was with his pipes and equipment, there might be a chance of the company men scrambling out in front of him, and so – to use his own words – “Bring disgrace on a Highland piper.”

“Well, if you think that way,” said the sergeantmajor, “ask the company commander to allow you to climb out before us.” This the piper did, and when the barrage opened he led off the advance, well ahead of the attacking wave, playing his pipes.

Blue Line

LCpl Alexander MacGillivray’s gallantry in the assault a source of inspiration to the troops on a wider battle front than that of the 16th. At the “Blue Line” when the Brigade attack reforming under fire for the further advance this piper played without ceasing. He marched up and down before the 16th companies and then strode off to the front of the 13th Battalion (Royal Highlanders of Canada) where, as described in the following extract from the history of that Battalion, he made a profound impression:—

“Just at this time,” the story reads, “when all ranks feeling the strain of remaining inactive under galling fire, and when the casualties had mounted to over 100, a skirl of the bagpipes heard, and along the 13th front came a piper of the 16th Canadian Scottish. This inspired individual, eyes blazing with excitement, and kilt proudly swinging to his measured tread, made his way along the line, piping as only a true Highlander can when men are dying, or facing death, all around him.

“Shell fire seemed to increase as the piper progressed and more than once it appeared that he was down, but the god of brave men was with him in that hour, and he disappeared, unharmed, to the flank whence he had come.”

Final Objective

McGillivray was also one of the men who overshot the final objective. When well ahead of the rest of his comrades, set upon by a German. To defend himself he dropped his pipes, and later, when his enemy disposed of, could not find them. He was very much worried over this loss and refused to go back to Battalion HQ, as all pipers had orders to do immediately the assault was over. Ultimately persuaded to return on the promise by the company sergeant-major that he personally would look for the pipes and take charge of them. The sergeant-major found the pipes next morning about forty to fifty yards in front of the final objective.

He brought them back with him, but Alec McGillivray was not there to claim his beloved instrument. Seen to start from the front line on his return journey and then disappeared entirely from view – probably blown to pieces by a shell.

Vimy Memorial

LCpl Alexander MacGillivray MM commemorated on the Vimy Memorial – the location of his remains unknown.

However, his family still hopes his remains may be recovered.

Acharacle Memorial

L/Cpl MacGillivray’s memorial tablet located just a few yards from the croft in Acharacle where his family live to this day.

At the entrance to Achararcle Cemetery, Acharacle Memorial.

Contact CEFRG

More

- Home of CEFRG

- Blog

- CEFRG on FaceBook

- CEFRG on YouTube

- Soldiers and Nursing Sisters

- Units (Brigades, Battalions, Companies)

- War Diary of the 18th Battalion (Blog)

- 48th Highlanders of Canada

- 116th Battalion CEF – The Great War

- Les Soldats du Québec Morts en Service

- Montreal Aviation Museum

- Battles of the Great War

- Cases

- Cemeteries

- Memorials

- On This Day

- About CEFRG