The battlefield experiences of Corporal George Turner MM, 44th Battalion, CEF, in the Great War. Turner wrote of his life in the trenches to Colonial Commerce (vol. 28, no. 2 (28 February 1919)), providing a quintessential account of the 44th Battalion (New Brunswick).

Private William George Turner 219854 born in St. John’s, Newfoundland on 25 June 1894. He enlisted on 1 October 1915 with the 80th Battalion, CEF at Belleville, Ontario. Transferred to the 74th Battalion, and then the 10th Brigade Machine Gun Company, he soon found himself deployed to the 44th Battalion, CEF, on 7 August 1916.

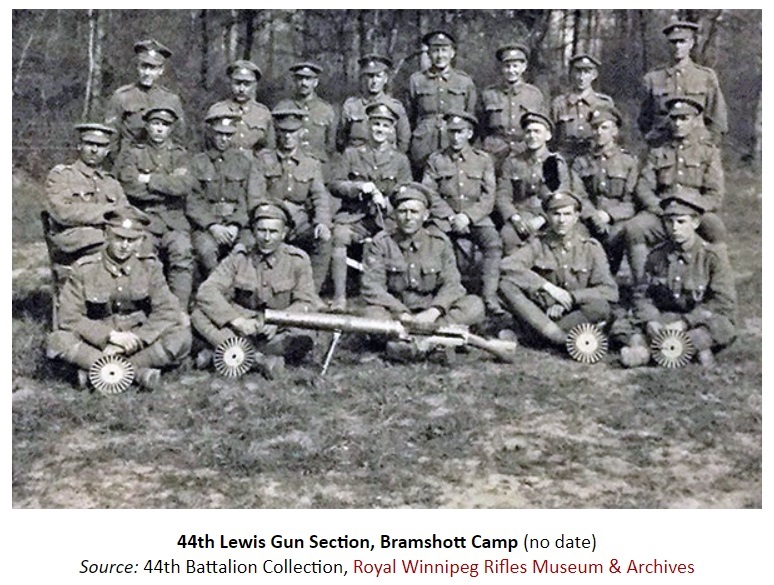

44th Battalion

Organized in February 1915 under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel E. R. Wayland. Mobilized at Winnipeg, and also recruited in Winnipeg. A draft of 5 officers and 249 other ranks sent to England on 4 September 1915, and a draft of 10 officers and 500 other ranks from 44th and 45th Battalions sent to England on 1 June 1915. Embarked from Halifax 23 October 1915 aboard SS LAPLAND, and disembarked in England on 30 October 1915 with a strength of 36 officers, 1076 other ranks.

The 44th Battalion disembarked in France on 10 August 1916 with the 4th Canadian Division, 10th Canadian Infantry Brigade. In August 1918, the 44th Battalion renamed the 44th Battalion (New Brunswick), CEF.

First Action

On the night of 20 August 1916 my company made their first trip and I don’t think I will try to analyze anybody else’s feelings as my own, I think, are a pretty good sample. Was I scared? Well! That’s putting it rather mildly. Every whine or whistle of a machine-gun bullet my heart just came up in my mouth, and considering they were crossing over our trenches in a steady stream, my heart changed places pretty frequently during my instructional tour.

Our platoon, No. 8, got up as far as the support line when we met a working party of the 21st Battalion and got held up in the trench, while our party sat on the firing step waiting for orders or a guide to conduct us back to our right position.

Pity

The Sergeant in charge of the party evidently read our thoughts and tried to make us feel at home by telling us what little chance a fellow ran of being hit. That our fears mostly our own imagination, when a stray one got him through the throat and down he came at my feet, without a sound except the gurgle of blood in his throat, and never spoke a word afterwards. The sight of death for my first time turned me sick Little I thought of the time I would get used to seeing a fellow cash-in with no other feeling except one of pity.

Well, our first tour came to an end with no other excitement, and then started our general round of trench work, which lasted for about a month, in the old Verstraat sector, which was about the quietest one on the whole front at the time.

Somme Offensive

After a month of this, the Canadians left for the Somme offensive, which started on July 1st, and we arrived on the scene on October 8th, after marching here from Ypres, with the exception of a short train ride from St. Omer.

Albert

The day we arrived at Albert it rained all day and we got our first break at the big war. Tarpaulins given us on the old brick fields just west of Albert, and told here was our bed for the night, and proved to be for three or four. Well, we made the best of it and I don’t think we lost much sleep thinking about the mud.

Our first trip in the Somme sector was fairly good ; the weather was ideal, and shelling not too heavy, so the boys came out saying it was not such a bad war after all.

Courcelette

Not so our second tour. We took up our position in trenches just south of Courcelette. Anybody who has been there will know them—the old sugar-and-candy trenches. During our stay here it rained for four days in a steady downpour; trenches were to a man’s waist in mud and water. There were no dugouts, and Fritz gave us a warm welcome. Well, like everything else, a fellow’s enjoyment must come to an end, and at last we found ourselves out again and preparing for our attack on Regina trench, which was staged for 24 October 1916, but postponed ’till the 25th as the units not in position in time.

The night of the 23rd, what few men left out of the line when the battalion went in a couple of days previous called up and from nine the night of the 23rd to 7 a. m. on the 24th the boys ploughed through mud to their hip, with ammunition, bombs, rations and other necessaries for the show, reaching the line more dead than alive.

Regina Trench

At daylight on the morning of the 25th the attack started, but, owing to lack of artillery support and machine gun fire, the show was a failure and the bunch got a bad shake, losing some of our best officers and men.

- Major William Henry Grant (ADANAC)

- Lt Frederick Averill Hall (Albert Communal)

- Lieutenant William Russell Notman (VIMY MEMORIAL)

- Lt William Robert Wilson (ADANAC)

After this stunt life on the Somme just one continual hell for us, between the shelling from Fritz and the mud. I may safely say about the hardest conditions men out here suffered for the following six weeks, although only one other attack staged by our brigade, and that by the 50th Battalion, gaining Regina trench which had been attacked at least ten times previously without success.

Vimy Ridge

From this front we moved to the sector which afterwards became known as the Canadians’ home, namely, Vimy Ridge. We took up our occupation here about the end of December—Christmas night, to be exact—and we sure got all kinds of greeting from the wrong source, which cost us about 60 casualties and made life a regular hell for about eight hours.

10th Canadian Trench Mortar Battery

From 23 December 1916 to 30 March 1917, Corporal George Turner attached to the 10th Canadian Trench Mortar Battery.

Everything on the Ridge went OK. A few raids pulled off during the spring of 1917, all of which were very successful, with the exception of one gas, which was not, as the wind changed, and we got the benefit.

Battle of Vimy Ridge

This brings us up to the Vimy show, which turned out such a success. We moved into place in an old tunnel, with about two feet of water in it, and camped here ’till five the next afternoon, when we got orders the show was off and we would be relieved. But, our joy short-lived, as the next happening was word that the 11th Brigade in difficulties and we would have to give them a helping hand in the capture of Hill 145, just south of us. Moved over during the night to Music-hall trench, where we rested ’till noon.

Sight to see

We then got orders for the attack, and got into formation right there, although we were at least 2,000 yards from the enemy. Say it was a sight worth seeing; a couple of battalions, strung out in waves, advancing with bayonets flashing, and the roar of the barrage, smoke of bursting shells, and multi-coloured signal flares of all possible hues.

Well, all that is necessary to say is that we did the job and relieved at about eight that night, when we moved back to Cabaret-rouge for the night. The following night we moved into position for our attack on the Pimple, which came off about an hour before daylight the next morning during a terrific snow storm which, in my opinion, saved us from annihilation, as Fritz sure had enough machine guns to stop an army, let alone a battalion.

The Pimple

After our very successful attack on the Pimple, which terminated the renowned Vimy Ridge battle, we left the line, relieved by an English battalion, and proceeded to Bouvigny to rest and receive fresh reinforcements to fill our depleted ranks. Our anticipation of a rest sadly smashed after our first night. At 6.30 our first morning in billets Reveille sounded by Fritz in the form of the old familiar screech of a high-velocity shell, ending in a crash as it struck the Chateau a hundred yards from our sleeping quarters.

Good things never come alone, and a very few minutes before the first shell followed by many more, all landing around the Chateau and grounds. This piece of good humor of Fritz’s kept up at intervals for the next six days, when the powers that rule the destinies of the army decided we must be thoroughly refreshed after such a perfect rest, and ordered our battalion to relieve the East Surreys, then holding the line in that position which shortly formed part of the well-known (and well cursed) triangle, where our boys fought so well from the end of April to the middle of June.

Triangle

Everybody’s tour in the triangle a thing to be remembered all one’s life. For a month and a half of hell, I doubt if it can be surpassed on any sector of the Western front – not even excepting Verdun, where our French brothers-in-arms made such a glorious stand against about the heaviest odds imaginable.

- Major Charles Stuart Belcher MC (Villers Station)

- Lt Elton Culbert Allin (Villers Station)

- Lt Moses Oliver (VIMY MEMORIAL)

- Lieutenant Mowbray MacDonnell Perdue (VIMY MEMORIAL)

- Lt Henry Alexander Robinson (VIMY MEMORIAL)

- Lt Harold Osborne Ross (VIMY MEMORIAL)

Flamethrowers

During those hot and feverish days in the Triangle, never a quiet hour from morning to morning, just one continuous thunder of artillery; high explosive bursting on all sides; the air poisonous with the fumes of cordite and gas; the atmosphere reeking with the smell of decomposed bodies (as in that heat a fellow was unapproachable after he was dead an hour)—our boys stood up to Fritz, breaking counter-attack after counter-attack for eight days in one stretch, and never gave him a footing in our trenches for more than a few minutes, except on one occasion when he used liquid fire.

Heathenish weapon of war

This heathenish weapon of war, if such it can be called, enough to put the fear of God in the hearts of the strongest men. Place yourself in our position and see how enviable it was, standing in narrow ditches, rotten with dead and crammed with dying. Suddenly, around a traverse, appears a whitish flume and everything ahead and in reach of it seems to vanish; then, a minute later, the Fritz operating it is seen walking along the trench spraying his deadly liquid ahead of him. You don’t have long to think and act, but at such times it is not needed: a fellow’s main object is to keep out of reach. The old proverb holds good out here “Self preservation is the first law of Nature.”

Of course after the first scare is over, and you have put enough distance between yourself and that vision of Hell, your thoughts are naturally cooler and plans are formed to eject the unwelcome visitor, which generally takes some doing, as he is very unwilling to move, and more good men go-west in the operation.

La Coulette

After our hardest days of fighting in the Triangle it was decided to attack La Coulette, and so improve our position, but here again we met with such opposition that we had to be relieved to re-organize, and did not gain possession of this town until the night of June 25th, when the enemy evacuated it, owing to our incessant artillery fire making it too costly for him to remain longer.

- Major William Robert Green (Villers Station)

- Lt Tuffy Wallace Anderson DCM (Barlin Communal)

- Captain Sydney Stibbard (VIMY MEMORIAL)

- Lt James Watson Potts (Villers Station)

- Lt S S Smith (VIMY MEMORIAL)

Green Crasseur

From June 25th until August 1st there is nothing very important to record. We were in rest in Hersain-Coupigny and everyone enjoyed himself to the utmost. Then we were employed as Flying Brigade, in reserve until the Green Crasseur show in front of Lens on August 25th, where we met one of the Heinie’s picked regiments and had a warm scrap of it; gained the slag heap, but, owing to heavy casual- ties and no support, had to retire at night to our old position.

After the Crasseur show our share of the fighting came-back to the old trench scrapping—blowing one another out with trench mortars of all sizes—and artillery straffing. This continued until well into September, when we started on the march again for the north, to take part in the offensive – then taking

place around Passchendaele.

- Captain William Jesse Edward Howard MC (Barlin Communal)

- Lt Frederick William Bradford (VIMY MEMORIAL)

- Lt Daniel James Broadfoot (VIMY MEMORIAL)

- Lieutenant Andrew McKay Gunn (VIMY MEMORIAL)

- Lt Henry McClure (VIMY MEMORIAL)

Passchendaele

The battalion marched from the Merricourt sector to a little town about 20 kilometres from Ypres, where we rested for about ten days to recuperate after the march and organize for the coming show. Our stay around this little town came to an end only too quickly, and very soon we found ourselves preparing for another slap at Fritz.

Crest Farm

One night towards the end of October—the 23rd, I think—we moved to the support position in the Passchendaele sector to uphold the 46th in their attack on Crest Farm and relieve them if they received too many casualties to hold the position after taking it. The attack launched about day-break, but the battalions in front received so much opposition that they never reached their objective and had such a bad smash that we took over the line that night in case the enemy decided to attack.

- Major Ralph Russell James Brown (Nine Elms British Cemetery)

- Lt Warner T Bole MC MM (MENIN GATE)

- Lt Charles Lucas Jeffrey (MENIN GATE)

- Lieutenant Arthur Loft (MENIN GATE)

- Lt Charles Stuart-Bailey (Nine Elms British Cemetery)

Capture of Passchendaele

We remained in the line awaiting developments for two days; then came the orders that we would make a night attack for the same objective, which we did at midnight. Fritz put up a good scrap, but it did not avail him anything ; our boys just walked away with him and by daylight the Canadians held all the high ground overlooking Passchendaele, which we successfully attacked and captured a couple of days later. The remainder of our stay around here taken up in working parties and putting up with his shelling and bombing. I won’t attempt to, as anyone would call me a liar if I stated the actual facts about it, except the fellows who experienced it. Well, after a couple of weeks of this our tour in d— old Passchendaele came to an end—(that ” D ” does not stand for dear).

Houdain

We then moved to Houdain for a rest, which lasted till about the 21st December, and all, I think, enjoyed themselves thoroughly, from there to the Chateau de la Haie, where we spent Christmas, and moved again to the front line on New Year’s Eve – started the New Year right, eh ?—for another round of trench warfare. Nothing of interest, except a raid or two, happened on our first two trips in the Avion sector.

We then took our position on the Lens front, until the our right flank resting on St. Louis Crater, and spent some more monotonous days, with the exception of one when Fritz raided us after stand-down and killed the officer in charge of a post. If you want the comical side of this you should talk to Corp. L. E. I. will tell you his name when I get home.

Amiens

This old round of routine went on from New Year till August 8th, when the Amiens show started. During the intervening time we occupied the Oppy sector, Lens, Merricourt, and spent a month in rest.

The 44th Battalion arrived at a little town called Dury on the morning of August 7th, at 5 a. m., when we got a few hours sleep to refresh us after the hard march south from Arras. At 11 a. m. the Commanding Officer, Col. Davies, called us all together for a last talk and final instructions previous to starting for our jumping off” positions for what turned out to be the biggest and best organized offensive

staged on the Western front, either by us or the enemy—namely, the battle of Amiens.

Gentelle Wood

After having the disposition of the various units taking part, the width of the front, depth of advance and objectives of each Division and Brigade, we received our orders to pack us, draw rations for three days, and prepare to move at dusk for a trench in the rear of Gentelle Wood, which proved to be the support line.

Zero Hour

We arrived there (Gentelle Wood) at 1 a. m. on August 8th, and sat around ’till the show started. At 4.13 a. m. the artillery opened for miles—in fact, as far as it was possible to see the horizon was one line of fire and everything pointed to a successful operation.

The infantry kicked off at 4.53 a. in., supported by tanks (six to a battalion frontage) and carried everything before them. This was the 1st Canadian Division. At 5:00 am, our Division, the 4th, started forward following up, and it was sure some hike. We marched until dark and only got within sight of the scrapping once, and that was only a small cavalry charge against a few machine guns in a

village. At dark, on August 8th, the battalion halted for the night in a defile west of Quisnel and north of Valley Wood. This defile showed signs of hard fighting, as the ground pretty well covered with dead, both men and horses.

9 August 1918

The second day (August 9th) broke fine and clear and I got a good job. My chum and I sent forward with a field telephone in the rear of the forward battalion position, to observe their attack on Quisnel and report it in detail to our Colonel, who was stationed in a trench at our battalion assembly position. We got up without any accident or incident worth writing about, and only had a wait of five minutes and a smoke when every gun on the Western front seemed to be shooting over our heads and making things a general hell in Fritzies line.

Cavalry Charge

This only lasted about twenty minutes when everything became quiet and the 12th Brigade of our Division launched their attack on the village, followed by a beautiful charge by a detachment of cavalry. I think I can safely say it was one of the finest sights I have seen out here. The machine gunners would run about twenty or thirty yards, then drop and get their guns into action, while the rifle sections, bombers, etc., advanced. This mode of advance continued until the whole outfit was within fifty yards of the town, when, at a given signal, the whole battalion made the finest rush I ever witnessed (it had a rush at Rugby beaten forty ways), and took the town.

The afternoon of the same day our battalion got orders to prepare to move forward as we were to attack in the morning, so everything became hustle

and bustle again, getting equipment, machine guns, carriers loaded, rations drawn and a thousand other things too numerous to mention.

Beauford

Well, we moved off at 2 p. m. and took a route slightly to the south of Quisnel and saw the French in a good swift scrap with a bunch of Heinie’s machine gunners, and they seemed to be having a very unpleasant time. We arrived at a little railway station just west of Beauford at 6 p. m. and made our H. Q. there for the night.

10 August 1918

August 10th—Everybody feeling fine and our show comes off to-day. At 3 a. m. the 44th Battalion left the railway station, marching east. At 4 a. m., while resting at Beauford, we met our Second-in-Command, Major Marty, with the field kitchens, and enjoyed a good hot breakfast. The only thing that spoiled our appetites was one shell which Fritz placed too close to one kitchen and which punctured a cylinder of porridge and knocked out an officer and a couple of privates. After our meal we moved to our assembly position for the attack, a road behind the wood at Warvillers, where every body present received a good jolt of rum before starting on our little joy ride.

18 Kilometer Advance

Where we started our attack from was eighteen kilometres into Fritz’s original front. By this time we had him backed into the old trenches, which comprised the Somme defences, which were just one too many for us in the fall of 1916. The objectives for four battalions in the Tenth Brigade were a depth of about four or five kilometres into these defences. So we all knew it was going to be far from a Sunday School picnic, and we were not disappointed.

First Village Liberated

Our outfit got along fine until a couple of hundred yards from the first village, when things began to happen. Fritz got nasty with a half dozen machine guns from concealed positions, and casualties were coming too fast to keep track of. The three lads with me all got knocked out within a space of three minutes. This state of affairs continued for about an hour and a half and, consequently, the battalion held up until the artillery got on the job and made a mess of things, when everything once more became sunshine and we went forward without any difficulty and gained all our objectives, but finished with three hundred and fifty less than we went into action with in the morning.

- Lt Gordon McMichael Matheson (Rosieres Communal)

- Lieutenant Horace Parker (Boves East Communal)

- Lt Alexander Turner (Fouquescourt)

The following day relieved and went out to Rosieres for a few day’s rest, feeling darned lucky to have whole hides.

Amiens Aftermath

From August 11th to August 27th nothing startling happening—only the usual round of pleasure, being bombed by aeroplanes at night, shelled during the day and, between times, the usual inspections, arrivals of reinforcements, and general re-organization for the next show.

Boves

On August 27th we left Boves (a little station south of Amiens) by train for the big scrap east of Arras, to take the Drocourt-Queant Switch, one of the main points on the Hindenburg line. Our battalion left Boves at 7.15 p.m. of August 27th, and arrived at Aubigny at 8.15 the following morning, where met by a convoy of lorries and taken through Arras.

- Lt Charles Frederick Blackburn

- Lt M K Burrows

- Lieutenant Alan Collie MC

- Lt N E Denham

- Lt A J J Flook MM

- Lieutenant William Brown Leslie

- Lt W G Vibert

- Lt Reginald Prinsep Wilkins

All of the above Lieutenants buried at Quarry Wood Cemetery, Sains-les-Marquion.

Naours Caves

We then marched three or four kilometres to the famous Caves, from which the material of Arras built. They are large to accommodate at least a division. We rested here over night and left on the morning of August 29th, but only moved about six kilometres east where we met some of the 2nd Canadian Division and heard from them that the show had started and that the famous Hindenburg line had been broken. From the 29th to the night of September 1st it was just a case of waiting with as much patience as possible for the eventful moment to arrive.

Remy

On the night of September 1st my battalion moved forward to its assembly position, just east of a little town called Remy, and I think we had about as rotten a night as I ever spent. Fritz was in his worst possible humour and gave us a pleasant walk in. He was bombing the road, shelling it with heavies and gas, and he sure had our wind up properly, but we reached our appointed place and lay in

shell craters and any other place of cover we could find till zero.

2 September 1918

At 5 a. m. on the 2nd the barrage started and it was a peach, just one continuous

roar—not a break in it from the second it opened ’till 5.20, when it lifted from his first to his second line and the tanks and infantry got into action. We reached his front line without any difficulty as his men were so demoralized that their officers could do nothing but surrender with what few men were left alive, and these were not a great many, as our artillery fire was murderous. I never saw such a shambles on any sector of the front, and I have seen some pretty bad messes out here. His men were just blown to pieces.

Dury

After cleaning up what few dug-outs our artillery failed to blow in, we advanced to his second line, just in front of Drury, and that’s where we very nearly met our Waterloo. Fritz managed to get a couple of machine guns placed so as to cover

advance nicely, and sure handed it to us while crossing some open country. Through lack of reinforcements we had to camp here ’till the morning of the

3rd, and what he did not do to us during the night is not worth mentioning.

Ecourt St Quentin

At 5 o’clock on the morning of the 3rd we made another kick off and captured Recourt without much opposition and advanced our line to the Sensee River, just west of Ecourt St. Quintin, where we got some very heavy shelling–in fact, we were so close to his field guns on the night of the 3rd that it was possible to hear his N. C. O’s giving the fire orders—a far from enviable position to be occupying.

Relief

We held the line here until relief arrived in the shape of the 52nd Canadians and Black Watch, when we moved to the rear for a few days’ well earned rest. This was on the night of September 5th. From September 5th to the 19th it was just the usual army routine–guards, fatigues, church parade and everything that makes a soldier forget his little worries out here.

Military Medal

Turner mentioned in the war diary on 9 September 1918 having been awarded the MM for operations at Fouquescourt.

Bullecourt

On the 19th we left Telegraph Hill and marched to Bullecourt, the scene of some of the hardest fighting of the war, and it is SOME town. If you searched morning

with a microscope you might, possibly, find one brick, and that is about all that is left of it. We camped at Bullecourt from September 19th to the 25th, so during this time there is nothing worth spoiling paper by writing about.

On the night of the 25th the 44th Battalion moved forward and took over the front line from the 26th, and spent just the ordinary “front line nights” the same old familiar sounds and sights.

Canal du Nord

On the 26th we moved B. H. Q. forward right into the line and after dark spread the battalion out in formation commonly used just before attacking, right out at our outpost line, and did not even attract the attention of our unfriendly neighbor once while doing it. I can assure you it is some job to get six or seven hundred men placed within one hundred yards of Heinie without his scenting trouble, but anyway we managed it.

Bourlon

The morning the Canal du Nord show was on, the attack was launched at 5.27 and by 6 o’clock we were interviewing our first prisoners at B. H. Q. From the time of starting ’till our first prisoners arrived was only about 33 minutes, so you see his infantry did not do us very much damage. We gained all our objectives in record time and when the 12th Brigade came up to continue the good work the some situation was clear as day, both flanks connected and no break anywhere, so they had no delay but attacked right away, and at 6 p.m. Bourlon was ours.

Cambrai

On the following morning our Battalion moved forward again and had another “slam” at him, advancing as far as the Douai-Cambria Road, capturing the village of Ralincourt on our way, and practically surrounding Cambrai on the North. So Fritz was beginning to get in a very awkward position.

Blighty

On Sunday, the 29th, our relief came in, so we the left the line for a while, (of course we all wanted to stay—I don’t think). The battalion came out minus about three hundred. From the 29th September to October 23rd, I won’t attempt to describe, as during that time I spent most of my time in Blighty, on leave, and there was only one show, of minor importance, during my absence from the battalion.

Lourches

On the 23rd October I got back to the battalion, then resting in Lourches, and stayed with them until the 29th when the 44th moved forward and took over the line from the Scotties in front of Chateau Fontinelle, just in time to drop in for a nice little counter-attack by Fritz,—just a little celebration to show how welcome we were. The battalion held the line here until the show started on the 1st November—the last scrap for this battalion, and a good one for a farewell.

Famers

The night before the curtain went up a bunch of us went into an empty house at Famars for the night and found a case of eggs and five live rabbits, so we spent the night making a good “breakfast” for the morning. After this, and getting our “issue,” we sure went over the top with full stomachs and light hearts.

Epilogue

The show turned out a success, as usual, and we got away with few casualties. Our relief arrived at night and we said good-bye to the war, as it was our last visit to the front line. Fritz quit before we could get another chance at him.

Corporal George Turner MM returned to Canada in 1919.

Contact CEFRG

More

- Home of CEFRG

- Blog

- CEFRG on FaceBook

- CEFRG on YouTube

- Soldiers and Nursing Sisters

- Units (Brigades, Battalions, Companies)

- War Diary of the 18th Battalion (Blog)

- 48th Highlanders of Canada

- 116th Battalion CEF – The Great War

- Les Soldats du Québec Morts en Service

- Montreal Aviation Museum

- Battles of the Great War

- Cases

- Cemeteries

- Memorials

- On This Day

- About CEFRG