Sergeant Arthur Knight not just witness, but a participant in the most tragic event for Canadians in the Great War. This is the story of the pain and suffering of a Canadian soldier awarded 3 Blue Service Chevrons serving with the Canadian Army Medical Corps. Sergeant Arthur Knight one of six CAMC soldiers posted to H.M.H.S. Llandovery Castle on 27 June 1918, the darkest day of the Great War for Canada.

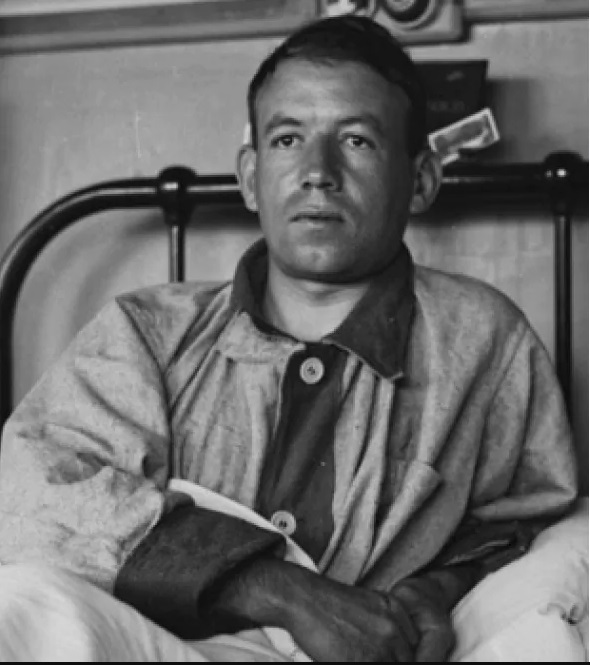

Sergeant Arthur Knight

Any soldier having spent a minute in the trenches knows the horror of war. Sergeant Arthur Knight is one of six Canadian soldiers with a unique outlook on the horror of war. He never made it to the trenches, serving in the CAMC shuttling patients on hospital ships between England and Canada. Witness to the pain and suffering of Canadian soldiers on a daily basis. In his duties, he also worked with the Canadian Nursing Sisters. He had no idea of the horrors which he had yet to experience.

What he witnessed, only rivalled by the bombings of Canadian Field Hospitals in France – the most harrowing days in the Great War for Canadians. Finally, CEFRG notes, the thousand-yard-stare reserved not only for soldiers in the trenches.

Sergeant Arthur Knight 528654 born at Brighton, England, 1 March 1886, and quit school at 11 years of age (7th Standard). Came to Canada later in March 1910 and worked at Casket Works, London, Ontario.

Enlisted 27 September 1915, London, Ont. ‘C’ Section, No. 2 Canadian Field Ambulance Depot. Next-of-kin, a friend, Miss Alice Dibsdale, 526 Nelson Street, London, Ontario. He was a Brass finisher. At this time, Arthur stood 5′ 2″ tall, with dark complexion, hazel eyes and dark brown hair.

Service

Private Arthur Knight sent to England in March 1916 and later served with No.2 Canadian Field Ambulance. Transferred to CAMC Moore Barracks for 11 months.

Private Arthur Knight admitted, Haematuria (blood in urine), 31 March 1916, Moore Barracks, Canadian General Hospital, Shorncliffe, Influenza, discharged 23 April 1916. Arthur’s medical record notes he has had such problems prior to his service. The condition will continue to cause him trouble from time to time.

H.S. LETITIA

Private Arthur Knight admitted 7 February 1917, Moore Barracks, Canadian General Hospital, Shorncliffe, Influenza, and later discharged 15 February 1917. Taken-on-Strength CAMC Depot, Liverpool, 10 March 1917. Beginning on 23 March 1917, Private Arthur Knight serves with the hospital ship H.S. LETITIA. Appointed to acting rank of Lance Corporal, Liverpool, 21 July 1917.

H.S. LETITIA ran aground on the rocks of Portuguese Cove, 1 August 1917. What followed a remarkable rescue operation. Many of the soldiers on board seriously wounded and could not move without help. Lance Corporal Arthur Knight helped to save the lives of some of the 546 wounded soldiers. Many military vessels, minesweepers and other vessels, engaged in the rescue.

H.S. ARAGUAYA

Given leave, and seeking a new posting, on 30 September 1917, Lance Corporal Arthur Knight granted permission to marry. Must be assumed all references in his record from this point to his friend, Miss Alice Digsby. Pay sent to wife as of 8 October 1917. On 12 December 1917, Lance Corporal Arthur Knight transfers to H.S. ARAGUAYA.

1 March 1918, appointed to rank of Corporal. Corporal Arthur Knight’s last day of duty on HS ARAGUAYA came 8 March 1918. Now on Command of No.5 Canadian General Hospital, Shorncliffe.

H.M.H.S. Llandovery Castle

On 21 March 1918, Corporal Arthur Knight posted to H.M.H.S. Llandovery Castle. Serves four months with H.M.H.S. Llandovery Castle, until ‘officially’ transferred to CAMC Casualty Depot on 2 July 1918. The events of 27 June 1918 will stay with Arthur for the rest of his life.

27 June 1918

Up until this time in the Great War, German U-boats would normally stop enemy ships, allow the passengers to disembark into life boats, and then torpedo the ship. However, the Great War now in the phase of the Final German Offensive. U-boat commanders under new orders designed to sway public opinion in Britain in favor of Germany suing for Peace. German High Command believed, as they had at the start of the Great War, atrocities could work in their favor. The first of these atrocities, in this campaign, the deliberate bombing of Field Hospitals in France.

With this change in policy, U-boat commanders ordered to ignore their usual tactics, and when the opportunity presented itself, to sink hospital ships without warning. However, U-86 Kapitän Helmut Brümmer-Patzig not yet a cold-blooded killer, and his conscious is troubling him.

He stopped H.M.H.S. Llandovery Castle, and interrogated the crew. Allowing the crewmembers to board their life boats, he then sunk the ship with a single torpedo. H.M.H.S. Llandovery Castle sank in less than ten minutes. Too fast, for one of the lifeboats could not get away from the scene, and sucked down by the whirlpool effect. On the lifeboat, 14 Nursing Sisters, and Corporal Arthur Knight.

Lifeboat No. 5

Corporal Arthur Knight, CAMC, one of twenty-four survivors of the disaster. The only survivor of Lifeboat No. 5. He later gave testimony at a war crimes trial in Germany about the nurses’ final comments. When he went to this trial, he was their voice, says his grandson David Sales.

Testimony Sergeant Arthur Knight

Sergeant Arthur Knight was on board Lifeboat No. 5 with the nurses. He testified:

Our boat was quickly loaded and lowered to the surface of the water. Then the crew of eight men and myself faced the difficulty of getting free from the ropes holding us to the ship’s side. I broke two axes trying to cut ourselves away, but was unsuccessful. With the forward motion and choppy sea the boat all the time was pounding against the ship’s side.

To save the boat we tried to keep ourselves away by using the oars, and soon every one of the latter were broken. Finally the ropes became loose at the top and we commenced to drift away. We were carried towards the stern of the ship, when suddenly the Poop deck seemed to break away and sink. The suction drew us quickly into the vacuum, the boat tipped over sideways, and every occupant went under.

Matron Margaret Marjory (Pearl) Fraser

Referring to Matron Margaret Marjory (Pearl) Fraser the daughter of Lt. Governor of Nova Scotia Duncan Cameron Fraser, Sergeant Arthur Knight continued his testimony.

Unflinchingly and calmly, as steady and collected as if on parade, without a complaint or a single sign of emotion, our fourteen devoted nursing sisters faced the terrible ordeal of certain death–only a matter of minutes–as our lifeboat neared that mad whirlpool of waters where all human power was helpless.

I estimate we were together in the boat about eight minutes. In that whole time I did not hear a complaint or murmur from one of the sisters. There was not a cry for help or any outward evidence of fear. In the entire time I overheard only one remark when the matron, Nursing Matron Margaret Marjory Fraser, turned to me as we drifted helplessly towards the stern of the ship and asked: “Sergeant, do you think there is any hope for us?”

I replied, ‘No,’ seeing myself our helplessness without oars and the sinking condition of the stern of the ship. A few seconds later we were drawn into the whirlpool of the submerged afterdeck, and the last I saw of the nursing sisters was as they were thrown over the side of the boat. All were wearing lifebelts, and of the fourteen two were in their nightdress, the others in uniform.

It was doubtful if any of them came to the surface again, although I myself sank and came up three times, finally clinging to a piece of wreckage and being eventually picked up by the captain’s boat.

Testimony Captain Kenneth Cummins

During the interrogation, for the benefit of his own crew, Kapitän Helmut Brümmer-Patzig adamant H.M.H.S. Llandovery Castle carrying munitions. A pretense, for what is to follow. U-86 begins ramming the lifeboats, then machine-guns to death the everyone in the water. However, Captain Kenneth Cummins’ lifeboat, now with Corporal Arthur Knight onboard, escapes detection.

Picked up by HMS MOREA, the survivors return to the scene and Captain Kenneth Cummins recalled the horror of coming across the nurses’ floating corpses;

We were in the Bristol Channel, quite well out to sea, and suddenly we began going through corpses. The Germans had sunk a British hospital ship, the Llandovery Castle, and we were sailing through floating bodies. We were not allowed to stop – we just had to go straight through. It was quite horrific, and my reaction was to vomit over the edge.

It was something we could never have imagined … particularly the nurses: seeing these bodies of women and nurses, floating in the ocean, having been there some time. Huge aprons and skirts in billows, which looked almost like sails because they dried in the hot sun.

Survivors

Six Canadians survived, along with 18 of the crew. The Canadian survivors, Major Thomas Lyon, Sergeant Arthur Knight 528654, Private George Robert Hickman 536288, Lance Corporal William Robert Pilot 69, Private Frederick William W. Cooper 522907, and Private Shirley Kitchener Taylor 536437.

Nursing Sisters Killed-in-Action

The names and birthplaces of the Nursing Sisters: Matron Margaret “Pearl” Fraser, New Glasgow, N.S.; Mary Agnes McKenzie, Toronto; Christina Campbell, Inverness-shire, Scotland; Carola Josephine Douglas, Toronto; Alexina Dussault, St-Hyacinthe, Que.; Minnie A. Follette, Cumberland Co, N.S.; Margaret Jane Fortescue, York Factory, Man.; Minnie Katherine Gallaher, Kingston, Ont.; Jessie M. McDiarmid, Ashton, Ont.; Rena McLean, Souris, P.E.I.; Mae Belle Sampson, Duntroon, Ont.; Gladys Irene Sare, England; Anna Irene Stamers, Saint John, N.B.; and Jean Templeman, Ottawa.

Recovery

After spending two hours floating with his injuries, Captain Kenneth Cummins’ lifeboat picked up Arthur. They drifted for another six hours before picked up by HMS MOREA. Communication sent to next-of-kin, Miss Alice Dibsdale, 4 July 1918, “A/Corporal Arthur Knight has landed safely – Llandovery Castle”. Alice was now living at 22 Wyatt Street, London, Ontario.

Canadian Convalescent Hospital, Bromley, Kent, 16 July 1918, Contusion of legs. On 2 August 1918, still complaining cannot sleep – no other complaint. Legs healed, looks pale. On 9 August 1918, still complaining cannot sleep. On 17 August, 1918 still complaining cannot sleep, blood in urine. At Massey-Harrig Convalescent Hospital, 24 August 1918, Pale, unable to sleep well. To transfer to No. 16 Canadian General Hospital.

Battle of Amiens

The ship’s name used as code word during the Battle of Amiens. I gave instructions that the battle cry on the 8th of August should be Llandovery Castle, and that that cry should be the last to ring in the ears of the Hun as the bayonet was driven home, said Brigadier George Tuxford, commander of the 3rd Infantry Brigade, quoted in Amiens: Dawn of Victory.

Sergeant Arthur Knight diagnosed at No. 16 Canadian General (Ontario Hospital) Orpington, Kent, 18 October 1918, unfit for service for six months. Discharged 8 November 1918, Neurasthenia. Admitted No. 5 Canadian General Hospital, Liverpool, November 1918, discharges 26 November 1918.

Sergeant Arthur Knight returns to Canada on a ship he knows very well, SS ARAGUAYA, 26 November 1918, disembarks on 7 December 1918 at Halifax.

Return to Canada

On 26 November 1918, Sergeant Arthur Knight’s medical file notes, In wreck on Hospital Ship 1 August 1917 then to Araguara, until March 1918 to Llandovery Castle, torpedoed 27 June 1918 170 miles off Ireland, two hours floating, then six hours in a small boat and picked up by a destroyer. Had pains in head, could not sleep. Legs bruised. More easily bothered by excitement now then before, dreams a lot of the water.

On 22 December 1918, Sergeant Arthur Knight awarded 3 Blue Service Chevrons, acknowledging his 36+ months of overseas service.

Discharged

Sergeant Arthur Knight at military hospital in London Ontario, 3 February 1919, treatment rest and massaging. Sent to Neurological treatment centre in Toronto, and returned 12 March 1919. Improved, and discharged on 18 March 1919 from His Majesty’s Service, as medically unfit.

Epilogue

Sergeant Arthur Knight died 1 December 1966, Essondale Hospital, BC, aged 80.

Captain Kenneth Cummins, last surviving Briton of both World Wars, died 10 December 2006. Survived by his wife Rosemary Byers, and their two sons and two daughters.

Kapitän Helmut Brümmer-Patzig fled Germany after the war, and not brought to trial. But, two of his lieutenants tried for war crimes, and sentenced to four years of hard labour. Later acquitted on grounds their captain solely responsible. Brümmer-Patzig served again commanding a flotilla at the end of the Second World War. He died in 1984, aged 93.

Two German U-Boats grounded near Falmouth in 1921. The one nearer to the camera UB 86, a UB III-class submarine commissioned on 10 November 1917, and made five patrols during the Great War (the hull number still visible). Surrendered to Great Britain on 24 November 1918. Broken up in situ near Falmouth after 1921, after grounding, together with UB 97, UB 106, UB 112, UB 128, and UC 92.

The original texts tells that these U-Boats washed ashore after sunk during the war (like U 118 at Hastings in 1919), but the lack of deck guns and periscopes shows that these boats already on the way to the breakers.

Atrocities

The atrocities which bookended the Great War, especially those of August 1914, largely forgotten. The sinking of H.M.H.S. Llandovery Castle and of course, RMS Lusitania, perhaps exceptions. Following the Armistice, Sir Arthur Currie met troops of the Canadian Corps awaiting demobilization in Andenne, Belgium on 31 January 1919. Following his speech, he visited the cemetery and memorial for the victims of the Andenne Massacre.

Andenne Massacre

Sir Arthur Currie did not forget this atrocity, even though the Canadian Corps had yet to reach the Western front in 1914. The following video presents the story of the “Rape of Belgium”, and the Andenne Massacre – Sir Arthur Currie Mémoire d’une Ville Martyre.

The hardest-hit places were Aarschot on 19 August and Andenne on 20 August; the small industrial town of Tamines on the Meuse, where 383 inhabitants killed on 22 August; the city of Dinant, where, on 23 August, the worst massacre of the invasion left 674 people, one out of every 10 inhabitants, dead; and the university town of Louvain (Leuven), where the treasured university library burned and 248 civilians killed.

Further south, hundreds of people executed in the Belgian Ardennes; on one occasion 122 alleged francs-tireurs killed in groups of 10; the last ones had to climb on the mound of corpses to be shot. On a smaller scale, invaded France experienced similar killings: the first civilians shot in the northern Meuse-et Moselle on 9 August, and, among other massacres, 60 people killed in Gerbéviller, a large lorrain village, on 24 August.

Throughout, the invaders made a point of stressing their superiority. One makeshift triumphal arch in the small town of Werchter, north of Louvain, built close to where the victims of a group execution lay buried, bore the inscription ‘To The Victorious Warriors’.

More

On 3 October 1916, SS GALLIA left Toulon unescorted, destined for Thessaloniki in Greece. Aboard 2,350 souls (1,650 French soldiers, 350 Serbian soldiers, and 350 crew members) and a cargo of artillery, and ammunition. The next day, between Sardinia and Tunisia, SS GALLIA torpedoed from the German submarine U-35 commanded by Lothar von Arnauld de la Perière.

SM U-35 was the most successful U-Boat of the Great War, amassing 539,741 gross tons for 224 sunken ships. Under command of Lothar von Arnauld de la Perière, SM U-35 sunk 195 ships, making Perière the most successful U-Boat commander of all-time.

Comments

One response to “Sergeant Arthur Knight in the Great War”

Hi,

Very sorry to bother, but I was wondering about the sources for this blog…..in most accounts I’ve read U-86 didn’t surface until AFTER firing on Llandovery Castle and did not stop her first, or give the crew time to abandon ship. Apparently Patzig did interrogate the ship’s Captain (R.A. Sylvester, not Kenneth Cummins – who was serving in HMS MOREA), but after the sinking. Cummins also died in 2006, not 2016 (a typo I’m guessing).